Getty Images | NurPhoto

A chapter in the ongoing Epic v. Apple court case closed yesterday when the US Supreme Court declined to hear further arguments from either company. This decision leaves the case where it was after the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled on it in April 2023.

The main issue at hand—to summarize days of arguments and multiple lengthy, technical court rulings in a couple of sentences—was whether Apple could continue to collect the 15–30 percent cut that it takes of all App Store purchases on its platforms and in-app purchases and subscriptions bought inside of those apps. The rulings, largely seen as victories for Apple, didn’t open iOS or iPadOS up to third-party app stores or app sideloading as Epic had originally sought. However, the rulings establised that Apple’s so-called “anti-steering” rules—language prohibiting developers from mentioning cheaper or alternative purchasing options that might be available outside of an app—were anticompetitive.

Apple has updated its App Store rules to allow developers to provide external links to other payment options, technically circumventing its normal fee structure. But they come with many extra conditions that developers have to meet. And instead of paying Apple a 15 or 30 percent cut, Apple will collect a 12–27 percent commission instead. After factoring in the fees from whatever non-Apple payment processor these developers decide to use, the revenue they give up will remain essentially unchanged.

Apple is still taking a cut

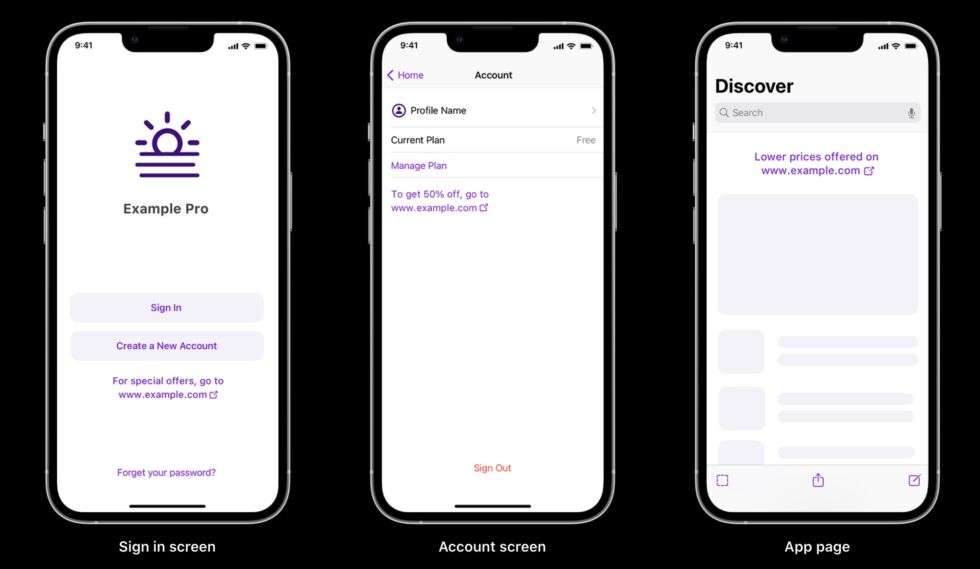

The new rules, which apply only to the US App Store, cover something Apple calls a StoreKit External Purchase Link Entitlement. This entitlement comes with a long list of additional requirements, which Apple says are “designed to help protect people’s privacy and security, prevent scams and fraudulent activity, and maintain the overall quality of the user experience.”

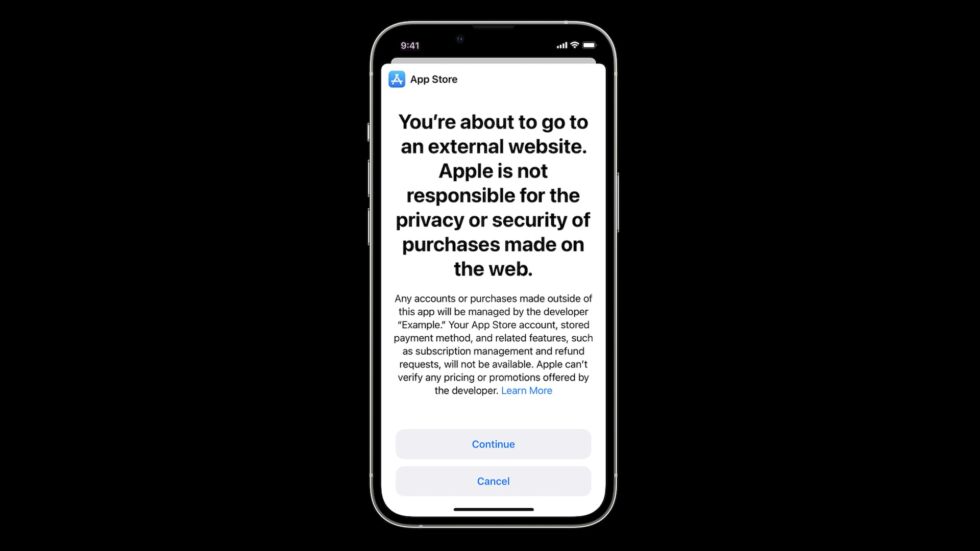

Most notably, external links must adhere to Apple’s “design and language requirements,” cannot “mimic Apple’s in-app purchase system,” and can only be displayed in one place in your app. Developers still can’t include language about going directly to their websites for a discounted rate. And whenever users click the external purchase link in your app, they’ll be shown a full-page warning screen explaining that Apple is not responsible for the site’s privacy or security and that you won’t be able to use your Apple account to manage purchases or subscriptions.

Apple

Developers who don’t get approval from Apple won’t be able to use this link entitlement and will be subject to the same rules and restrictions around external purchasing links as before. Developers who offer external purchasing links will also be required to offer standard in-app purchasing through Apple, and developers “may not discourage end-users from making in-app purchases.”

The new commission reporting requirements may be even more onerous, particularly for small developers. In short, devs who would have owed Apple 15 percent of any in-app purchases will owe Apple a 12 percent commission on any in-app purchases made using a third-party site. Developers who would have owned Apple a 30 percent cut will owe a 27 percent commission instead. Apple says that these commissions “account for the substantial value Apple provides developers, including in facilitating linked transactions.”

To put these rates in context, payment processors generally take a small percentage of all online transactions, plus a small fixed fee. Square and Stripe, to pick two prominent examples, take 2.9 percent of every sale plus an additional 30 cents (NerdWallet has a good comparative list).

Apple

Depending on what a developer is charging for in-app purchases, this could work out to a little under 3 percent or substantially more than 3 percent. Regardless, most developers would struggle to take home more money than they do by using Apple’s built-in payment system, especially once you factor in overhead for complying with Apple’s filing requirements. Developers will be required to file monthly transaction reports with Apple, and they will be invoiced based on those reports. Apple will charge interest on late payments, and if the company ever “develops an API to facilitate reporting,” developers will be required to add support in their apps within 30 days.

Developers who attempt to circumvent any of Apple’s requirements can have their apps removed and developer accounts suspended at Apple’s discretion.

The way Apple has structured this link entitlement is similar to a hypothetical suggested by Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers in the original Epic v. Apple ruling.

“Even in the absence of [in-app purchases,] Apple could still charge a commission on developers. It would simply be more difficult for Apple to collect that commision,” Rodriguez writes, before continuing in a footnote. “In such a hypothetical world, developers could potentially avoid the commission while benefitting from Apple’s innovation and intellectual property free of charge. The Court presumes that in such circumstances that Apple may rely on imposing and utilizing a contractual right to audit developers annual accounting to ensure compliance with its commissions, among other methods. Of course, any alternatives to IAP (including the foregoing) would seemingly impose both increased monetary and time costs to both Apple and the developers.”

Regardless of Apple’s intent, it seems clear that most developers will continue on the path of least resistance: use Apple’s first-party in-app payment system, which rolls Apple’s commission fees and payment processing fees up into a flat 15–30 percent payment, doesn’t come with the same restrictions or warnings as Apple’s External Purchase Link Entitlement system, and doesn’t require the same amount of administrative overhead.

And the new rules may open up another chapter in the Epic v. Apple saga. Epic CEO Tim Sweeney called the new rules a “bad-faith compliance plan” and vowed to contest them in district court.